Week One: Background

Patmos - John's Prison Island

The emperor Domitian never intended Patmos to be a place of revelation. He meant it to be a place of forgetting. The tiny, rocky island (only 10 × 6 miles) lies 37 miles off the Turkish coast. In AD 95 it housed a few hundred political and religious prisoners exiled “because of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus” (Rev 1:9). John, likely in his nineties, was one of them. Tradition says that on a Sunday, while “in the Spirit on the Lord’s day,” the risen Christ appeared in blazing glory and dictated the entire book. The cave where this happened is still visited today. Rome sent John to Patmos to silence him; instead, the silence of Patmos became the megaphone for the greatest unveiling of Jesus in Scripture.

Roman Emperor as Morning Star

Julius Caesar claimed descent from Venus, the morning star. Augustus minted coins showing a star over the Capitol with the caption “the divine Julius.” Domitian’s coins showed the morning star rising behind his head. Citizens were required to call him “Lord and God.” Against that backdrop, Revelation 22:16 lands like a thunderclap: “I, Jesus… am the root and the descendant of David, the bright morning star.” Jesus does not merely claim a stolen title; He reclaims the very symbol the emperors corrupted. The counterfeit falls; the true Morning Star has risen.

Seven Golden Lampstands

Most of us picture one seven-branched Jewish menorah. That is not what John saw. He explicitly saw seven separate golden lampstands (plural λυχνίαι, never menorah) with Jesus walking among them. Archaeology confirms the image: tall, elegant, single-spouted oil lamps on ornate stands, common in wealthy 1st-century homes across Asia Minor. Each house church owned one and placed it in the center of their meeting room. Seven churches = seven literal lampstands. The threat to Ephesus (“I will remove your lampstand”) is terrifyingly concrete, and the picture of Jesus moving from lampstand to lampstand is far more intimate than standing beside one big candelabra. Seven vulnerable local churches, one living Savior walking in their midst.

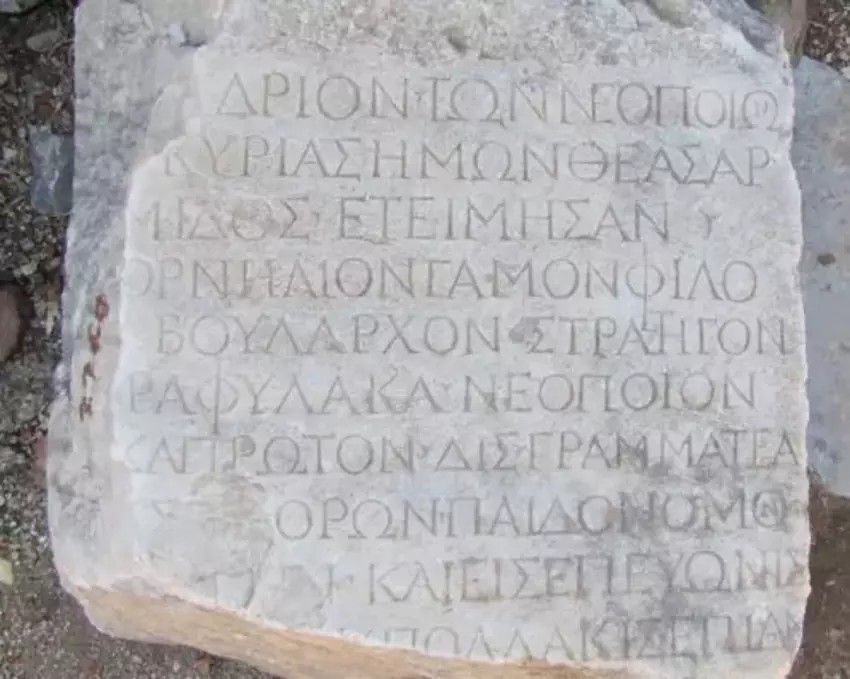

Domitian’s “Lord and God” Inscription

In Ephesus a massive limestone block still reads: “To the goddess Artemis… and to the emperor Domitian, Lord and God.” Domitian was the first emperor to demand the title officially in his lifetime. Refusing to say it could cost job, guild membership, or life. When Jesus begins each letter with “The words of him who…” He is hijacking the exact imperial edict formula. Roman couriers would read, “Thus says Caesar, Lord and God…” Jesus uses the same language to declare, “I, not Caesar, am the true Sovereign.”

The Marble Roman Road That Carried the Seven Letters

One of the finest highways in the empire, marble- or limestone-paved, colonnaded, with post stations every few miles, linked all seven cities. A lone courier rode it in eight days delivering the scrolls. That is the physical route. The Holy Spirit arranged the theological route as a perfect chiasm with Thyatira in the center. The empire built the road to move armies and taxes. Jesus borrowed it to deliver love, warning, and the offer of Himself. Sections of the original paving, complete with chariot ruts, are still walkable today.

A View Across the Centuries: Do the Seven Letters Sketch the Whole Story of the Church?

From the earliest church fathers (Victorinus, ~AD 270) to modern preachers, thoughtful readers have been struck by how neatly the seven letters appear to line up with seven major eras of church history.

Ephesus – The apostolic and immediate post-apostolic church (AD 30–100). Busy, doctrinally pure, yet already in danger of losing first love.

Smyrna – The era of the great Roman persecutions (100–313). Poor, slandered, facing prison and death, yet rich in faith.

Pergamum – The imperial church after Constantine (313–600). Christianity becomes the state religion, but compromise and pagan practices creep in.

Thyatira – The long medieval period (600–1500). Works-based righteousness, corruption, and a prophetic voice (Jezebel) tolerated in the church.

Sardis – The Reformation and post-Reformation centuries (1500–1800). A name for being alive (Protestant orthodoxy) but often spiritually dead.

Philadelphia – The great missionary and revival era (1800–mid-20th century). Little strength, yet an open door no one can shut — the gospel circles the globe.

Laodicea – The modern / last-days church (mid-20th century–present). Wealthy, self-sufficient, increasing lukewarmness.

This way of reading the letters is usually called the historical-prophetic or church-age view. It has been held by teachers as diverse as Augustine, the Reformers, the Puritans, and many 19th- and 20th-century pastors.

Important cautions:

- Jesus was first and foremost addressing seven real, local, 1st-century congregations.

- The “church-age” view is an observation, not a doctrine spelled out in the text itself.

- No single era perfectly matches every detail of its letter.

Yet the pattern is striking enough that it has encouraged millions of believers with this truth:

Jesus is not surprised by any season His church goes through. He already saw it coming, already spoke to it, and is still walking among the lampstands, trimming the wicks, calling us to overcome, and promising Himself as the final reward.

Whether we are in the Philadelphian open door or the Laodicean lukewarmness (or both at once!), the call is the same:

Hold fast. Repent where needed. Open the door.

The Morning Star is coming — and He wants His bride ready.

Discussion Questions:

- Which “era” do you think best describes the church in our city right now?

- Which characteristics of the other eras do you see creeping in?

- How does it encourage you to know that Jesus already knew every season His church would face?

"I Already Told You This”: How the Seven Letters Echo the Olivet Discourse and the Upper Room

Download the ChartThe seven letters are the risen Jesus applying His own pre-cross teaching

to seven real, first-century churches and to every church since.

The Pattern Is Deliberate

The Olivet Discourse is Jesus’ final public teaching before the cross.

The Upper Room Discourse is His final private teaching to the Eleven.

Revelation 2–3 is the risen Jesus saying, “Everything I taught you that last week is now being lived out in real churches under real pressure. You already know what to do

because I already told you.”

- Ephesus is warned the same way the sleepy disciples in Gethsemane were warned: “Could you not watch one hour?”

- Smyrna is promised the crown of life the same way Jesus promised the thief on the cross.

- Pergamum and Thyatira are facing the same false teaching Jesus warned about in Matthew 24.

- Sardis is asleep the same way the ten virgins were asleep when the bridegroom came.

- Philadelphia is given an open door (John 10:7–9 – “I am the door”).

- Laodicea is invited to intimate table fellowship the same way Jesus invited Zacchaeus and the two on the Emmaus road.

The Single Most Important Connection

The phrase that appears seven times in the letters

— “To the one who conquers” (ὁ νικῶν) — is lifted straight from the Upper Room:

“I have said these things to you, that in me you may have peace. In the world you will have tribulation. But take heart; I have overcome the world (νενίκηκα τὸν κόσμον).” (John 16:33)

Every promise to the overcomer in Revelation 2–3 is simply Jesus sharing the spoils of the victory He already won on the cross and in the resurrection.

For Us Today

When we read the seven letters and feel the weight or conviction, we are not hearing a new, harsher Jesus. We are hearing the same Jesus who wept over Jerusalem, washed feet, and said, “Let not your hearts be troubled.”

He already told us everything we need to overcome.

Now He walks among the lampstands to make sure we do not forget.

Discussion Questions

- Which warning or promise in the seven letters feels most like something Jesus already said to you in the Gospels?

- Read John 16:33 and Revelation 2–3 side-by-side. How does knowing Jesus has already overcome the world change the way you face today’s pressure?

- If Jesus showed up in your church this Sunday and began with “I know your works…”, what do you think He would say next?

Many Mirrored (Chiastic) Patterns Are Found in the Bible

The Bible is not just a collection of stories, laws, poems, and letters—it is a masterpiece of literary design. One of the most elegant and intentional patterns woven throughout Scripture is the chiasm, a mirrored structure where ideas or phrases are presented and then repeated in reverse order, often with a pivotal point in the center. The name "chiasm" comes from the Greek letter chi (Χ), which looks like a cross or mirror image. This technique is especially common in ancient Hebrew writing, where it served to emphasize key truths, create rhythm in oral traditions, and draw the reader's eye (or ear) to the heart of the message.

The Nature of Chiastic Structures

Chiastic patterns are like a sandwich or an arrowhead: the outer layers match symmetrically, folding inward to spotlight the core idea. They can span a single verse, a paragraph, a chapter, an entire book, or even multiple books. Scholars estimate there are hundreds—possibly over a thousand—chiastic structures in the Bible, from simple ABBA patterns to complex multi-layered designs. They appear in both the Old and New Testaments, in narrative, poetry, prophecy, and epistles.

The nature of chiasms is deeply intentional. In a culture without bold text or italics, ancient authors used symmetry to highlight what matters most. The center often reveals the theological bullseye: a command, a promise, a lament, or a revelation of God's character. For modern readers, chiasms bring clarity by tying disparate elements together, showing how the beginning and end of a passage echo each other, and focusing our minds on the central truth. As you noted, this mirroring not only sharpens the main point but also weaves the whole topic into a cohesive, memorable tapestry—much like how a well-composed symphony resolves its themes in harmony.

Why so many? Chiasms reflect the Bible's oral roots; they made memorization easier and added beauty to recitation. They also mirror God's ordered creation: balance, symmetry, and purpose. While not every biblical passage is chiastic, spotting them unlocks deeper layers, revealing the Spirit's artistry in inspiring human authors.

A Simple Case for Their Number and Prevalence

To make a straightforward case: chiastic structures are abundant because they fit the Hebrew mindset, where parallelism (repeating ideas for emphasis) was a core literary tool. In the Old Testament alone, Psalms and Proverbs are rife with small-scale chiasms, while narratives like Genesis and Exodus use larger ones to frame events. The New Testament, influenced by Jewish writers, carries this forward—Jesus' teachings, Paul's letters, and even Revelation employ them.

Conservative estimates from scholars like Nils Lund (in his 1942 classic Chiasmus in the New Testament) and John Breck (The Shape of Biblical Language, 1994) suggest at least 200-300 clear chiasms across Scripture, with many more subtle ones. Modern tools, like computer-assisted analysis, have uncovered even more, showing that about 20-30% of poetic sections and 10-15% of narratives may contain chiastic elements. Their nature is versatile: some are tight and obvious (e.g., a single verse), others expansive and subtle (e.g., entire books). They aren't accidental; they guide interpretation, often resolving debates by centering on God's sovereignty, human responsibility, or Christ's victory.

Listing Examples of Chiastic Structures

Here is a curated list of over 30 notable chiastic passages, grouped by Testament and genre. I've kept descriptions brief, noting the rough span and central emphasis without full outlines. These represent a fraction of what's out there—favorites like the Songs of Ascent are included, along with others for breadth.

Old Testament Narratives and Laws

• Genesis 1:1-2:3 (Creation Week) – Centers on the Sabbath rest as God's holy pattern.

• Genesis 6:9-9:17 (Noah's Flood) – Pivots on God's remembrance of Noah amid the waters.

• Genesis 11:1-9 (Tower of Babel) – Focuses on God's scattering to humble human pride.

• Exodus 3:1-22 (Burning Bush) – Centers on "I AM WHO I AM" as God's self-revelation.

• Exodus 20:1-17 (Ten Commandments) – Mirrors to emphasize loving God and neighbor.

• Leviticus 16 (Day of Atonement) – Pivots on the scapegoat bearing sins into the wilderness.

• Numbers 11:4-34 (Quail Incident) – Centers on God's judgment on ungrateful craving.

• Deuteronomy 28 (Blessings and Curses) – Focuses on obedience as the path to life.

Old Testament Poetry and Wisdom

• Job 3 (Job's Lament) – Centers on wishing he had never been born amid suffering.

• Psalm 1 – Pivots on the blessed man delighting in God's law.

• Psalm 23 – Focuses on God's provision in the valley of the shadow of death.

• Psalm 67 – Centers on God's blessing shining on all nations.

• Psalms 120-134 (Songs of Ascent) – Overall chiasm emphasizes pilgrimage from distress to divine blessing (detailed below).

• Proverbs 31:10-31 (Woman of Valor) – Acrostic chiasm centering on her fear of the Lord.

• Ecclesiastes 3:1-8 (A Time for Everything) – Mirrors life's seasons to underscore God's timing.

• Song of Solomon 2:8-17 – Pivots on the lovers' invitation amid spring's renewal.

Old Testament Prophecy

• Isaiah 6:1-13 (Isaiah's Call) – Centers on the holy God's cleansing and commission.

• Isaiah 40:1-11 – Focuses on God's word standing forever.

• Jeremiah 1:4-19 (Jeremiah's Call) – Pivots on God's promise to deliver amid opposition.

• Ezekiel 37:1-14 (Valley of Dry Bones) – Centers on God's breath bringing life to the dead.

• Daniel 2 (Nebuchadnezzar's Dream) – Mirrors kingdoms to emphasize God's eternal reign.

• Jonah 2 (Jonah's Prayer) – Pivots on Jonah's vow from the belly of the fish.

• Habakkuk 3 – Focuses on rejoicing in God despite calamity.

New Testament Gospels and Acts

• Matthew 5:3-12 (Beatitudes) – Centers on persecution for righteousness' sake.

• Mark 2:1-12 (Healing the Paralytic) – Pivots on forgiveness of sins as true authority.

• Luke 1:46-55 (Magnificat) – Focuses on God's mercy reversing the proud and lowly.

• Luke 15 (Chapter of the Lost) – Three parables mirroring God's joyful pursuit (detailed below).

• John 1:1-18 (Prologue) – Mirrors to emphasize the Word becoming flesh.

• Acts 2:14-41 (Peter's Pentecost Sermon) – Pivots on calling all to repent and be baptized.

New Testament Epistles and Revelation

• Romans 5:12-21 (Adam and Christ) – Centers on grace abounding over sin.

• Philippians 2:5-11 (Christ Hymn) – Pivots on Jesus' humility and exaltation.

• Hebrews 1:1-4 – Focuses on Christ's superiority as God's final revelation.

• Revelation 2-3 (Seven Letters) – Overall chiasm centering on Thyatira's Morning Star promise.

These examples span genres and eras, showing chiasms' versatility. They aren't exhaustive—books like Esther, Ruth, and Lamentations may be chiastic wholes—but they illustrate how prevalent the pattern is.

Detailed Illustrations of a Few Chiastic Structures

To bring this to life, let's illustrate three examples in detail: the Songs of Ascent (Psalms sung walking on the pilgrim journey to the temple), Luke 15 (the Chapter of the Lost—a simple, well-known New Testament gem), and Philippians 2:5-11 (a compact epistle highlight). For each, the structure is labeled (A, B, C for the outward layers), key phrases highlighted, and explanation of the central point's clarity.

Psalms 120-134: The Songs of Ascent

These 15 psalms were sung by pilgrims ascending to Jerusalem for festivals. The collection forms a grand chiasm, with Psalm 127 at the center. Here's the mirrored outline:

• A: Distress in exile (Ps 120)

• B: Protection from enemies (121)

• C: Joy in Jerusalem (122)

• D: Mercy from God (123)

• E: Deliverance from traps (124)

• F: Security in the Lord (125)

• G: Restoration of fortunes (126)

• H (Center): Unless the Lord builds the house (127)

– "It is in vain that you rise up early… for he gives to his beloved sleep."

• G′: Joy in restoration (128)

• F′: Security from affliction (129)

• E′: Forgiveness from iniquity (130)

• D′: Hope in the Lord (131)

• C′: Blessing in Zion (132)

• B′: Unity among brothers (133)

• A′: Blessing in the house of the Lord (134)

The center spotlights divine sovereignty: human effort is futile without God. This mirrors the pilgrim's journey from distant distress to temple blessing, tying the psalms into a unified ascent where rest in God is the peak. The structure clarifies that the true "ascent" is spiritual dependence, not just physical steps.

Luke 15: The Chapter of the Lost

This beloved chapter contains three parables responding to the Pharisees' grumbling about Jesus welcoming sinners. It forms a clear, elegant chiasm (ABA′ pattern) that ties the stories together and drives home God's heart for the lost.

• A – Lost Sheep (vv. 3–7)

One sheep out of 100 is lost. The shepherd leaves the 99, searches diligently, finds it, carries it home on his shoulders, and rejoices with friends and neighbors. “There will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance.”

• B (Center) – Lost Coin (vv. 8–10)

One coin out of 10 is lost. The woman lights a lamp, sweeps the house, searches carefully until she finds it, and rejoices with friends and neighbors. “Just so, I tell you, there is joy before the angels of God over one sinner who repents.”

• A′ – Lost Son (vv. 11–32)

One son out of two is lost (and later the older brother's heart is revealed as distant). The father waits, runs to embrace the returning prodigal, restores him fully with robe, ring, and feast, and rejoices. Yet the older brother refuses to join the celebration—highlighting the Pharisees' own resistance.

The short central parable of the lost coin emphasizes God's intimate, persistent, diligent search—even for something as small as a single coin in a dark house. The mirroring progression (1/100 → 1/10 → 1/2) shows the loss growing more personal, while the repeated joy with “friends and neighbors” ties the outer parables to the center. This structure clarifies the chapter's bullseye: Heaven's greatest celebration is over one repentant sinner, and God's pursuit is relentless and joyful. It also subtly indicts the grumblers, making the whole chapter a cohesive call to join the party rather than stand outside.

Philippians 2:5-11: The Christ Hymn

This poetic passage is a tight chiasm exalting Christ's humility. Outline:

• A: Mind of Christ (2:5)

• B: Equality with God not grasped (2:6)

• C: Emptied Himself, taking servant form (2:7a)

• D: Born in likeness of men (2:7b)

• E: Humbled Himself, obedient to death (2:8a)

• F (Center): Even death on a cross (2:8b)

• E′: God exalted Him (2:9a)

• D′: Gave Him the name above every name (2:9b)

• C′: Every knee bows in heaven, earth, under earth (2:10)

• B′: Every tongue confesses Jesus is Lord (2:11a)

• A′: To the glory of God the Father (2:11b)

The center crucifies our attention on the cross as the ultimate act of obedience. This mirrors descent (humility) with ascent (exaltation), clarifying that true glory comes through self-emptying service. The structure ties Paul's plea for unity to Christ's example, making the hymn a memorable call to humility.

Why Chiastic Patterns Matter Today

In a world of fragmented information, chiasms remind us that God's word is ordered and purposeful. They sharpen the central point—whether it's Sabbath rest, divine sovereignty, joyful pursuit of the lost, or the cross—and bind the whole into unity, much like how your mind connects themes in the Songs of Ascent or the Chapter of the Lost. Exploring them doesn't require a degree; just attentive reading. As you spot more, you'll see Scripture's beauty unfold, drawing you deeper into the heart of God.